Does your interest in the human condition come from a personal place, or has it developed on a more universal level?

My work is not autobiographical. I do not think it is possible to work around the human condition from an impersonal place; by it’s very nature it demands a response that comes from an emotional register, how it feels to be alive and this can only be personal. I think the prerequisite for engagement with my work–I am not talking about value judgement, knowledge or taste–is an engagement with what it is to be human. In this sense the ‘personal’ is ‘universal’.

Fluidity (of meaning, form, weight, reality) is a word often used to describe your work. Can you tell me a little about that?

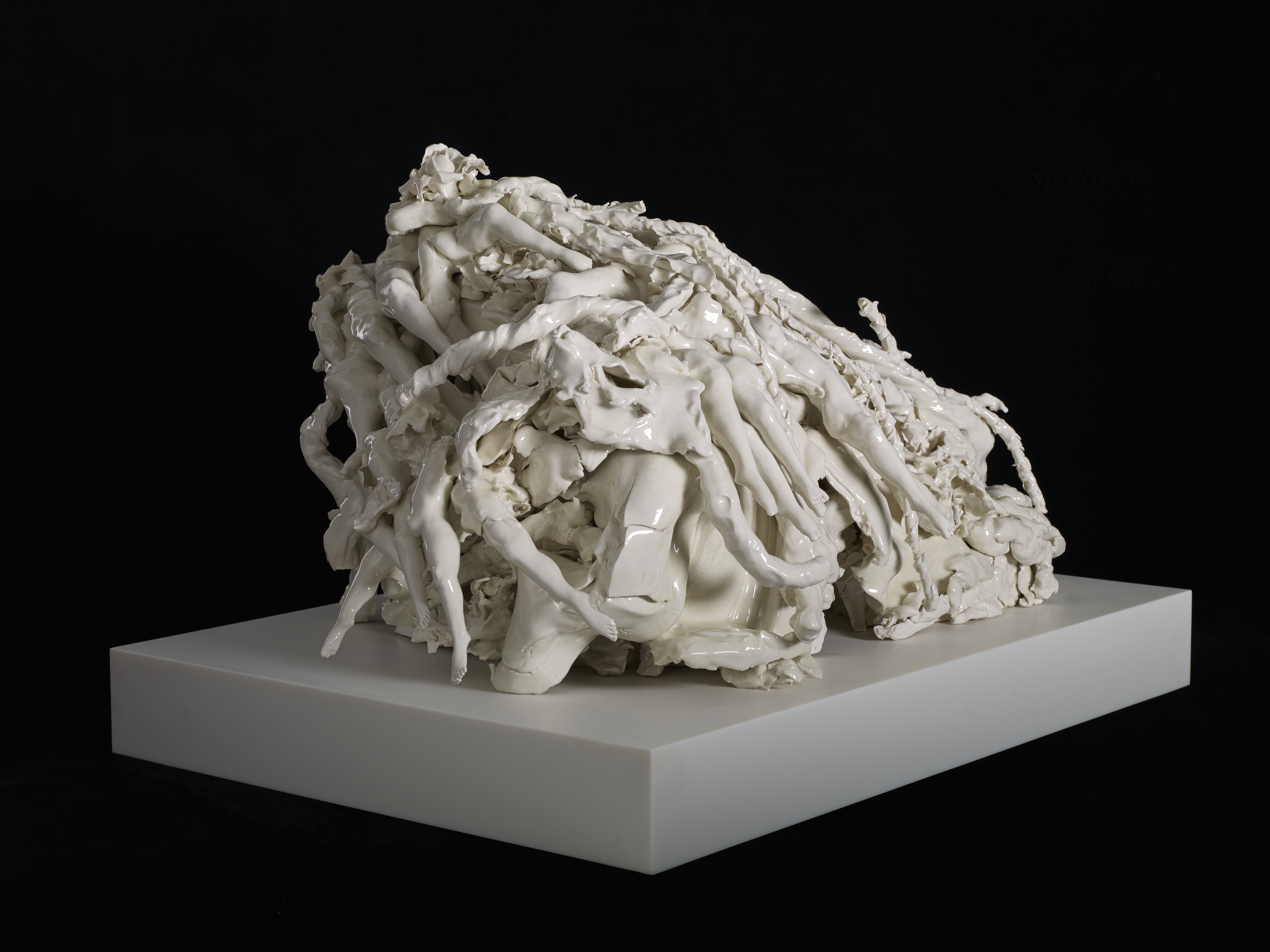

Fluidity is a mobile word, not static or fixed, and neither is the work in terms of its interpretation or meaning. I work around in-between states, transformation and metamorphosis, beginnings and endings, and each work embodies forces acting in multiple directions at once−in constant flux. Fluidity is the best means of articulating this active state in which the work, aesthetically and conceptually, is simultaneously forming and breaking.

You often reference the body in your pieces. Do you work from life?

In all ways.

How spontaneous are you with the pieces themselves? Do you have quite a regimented design process, or do they develop as they’re being built?

My work has never been the result of a regimented design process. But how I begin a work has undergone a significant metamorphosis. Initially I could not make until I knew my ‘start point’. This could be a feeling, a question I wanted to ask through making, a confrontation of forms. I needed to know this in order to begin. I would find the start point from drawing, looking at paintings, or maybe it would be triggered by something I had read. Once this was established I would begin and from that point on the work came from ‘problem solving’. Over time this requirement lessened and now I start work from working, and am led into a piece by a spontaneous response to form and material; the work is made through the act of making.

Porcelain is not a material commonly used by contemporary artists. How do you find it to work with?

Perhaps it is because porcelain is perceived as unusual that I am always asked to narrate my work through material, in terms of its material. In a sense I find this question perplexing, as I do not think that as a response to their work painters are so habitually asked to narrate paint. However, the materiality of my work is undeniable, without it my work would not exist. The correlation between material, the process of working with porcelain, and the concept of metamorphosis is integral to my practise. The porcelain body transforms from its initial malleable/plastic state, is then changed through the firing processes to a dry, hard form and ultimately the final vitrified body is simultaneously returned to wet–the quality of liquefaction provided by the glaze. Ideas around flux, change, movement, the ‘in-between’ states are all part of my general work enquiry.

Images courtesy the artist and White Cube.