The Bechdel Test, created by cartoonist Alison Bechdel in 1985, asks audiences to be critical of gender representation in fiction by querying: are there at least two main female characters who speak to one another about something besides a man? Later, in 2014, Nina Power, author of One-Dimensional Woman, wrote that it remained to be determined how often real life passes the test—as in, are women really having conversations on their own terms? The recent and startling proliferation of published work in various media by young women—often still in their teens and early twenties—delivers a resounding ‘yes’ by way of response.

This article originally appeared in Issue 25.

Recently, Tavi Gevinson—the 19-year-old editor of teen website Rookie—was invited to guest edit a section of one of the world’s most prestigious poetry magazines. It wasn’t the most reported project in her already storied career, which began when Gevinson started a blog aged 12 and was quickly propelled into the front rows of fashion week, looking endearingly awkward with pastel grey-pink hair and plastic specs. She’s since produced four annual issues of the Rookie Yearbook, maintained the website as editor-in-chief, and spoken at countless events about her experiences as an obsessively creative person. For more than one reason, though, this particular collaboration felt significant.

Literary magazines have traditionally been a fertile site of gender inequality, reinforcing endemic structural sexism by disproportionately publishing men’s voices. A study by American organization vida: Women in Literary Arts (who annually count numbers of female reviewers and reviews of female-authored books in big literary magazines) showed that, in the history of the London Review of Books, 82 per cent of reviews have been written by men. Though the LRB comes off a little worse than competitors like The New Yorker or the Paris Review, the picture is not so different right across the literary board.

So when Gevinson took the helm of Poetry magazine and wrote an introductory essay entitled ‘On the Uses of Teenage Angst’, she was not only working to bring young female voices into a traditionally male space, but also choosing to focus on exactly the quality that often gets the voices of young people, and particularly of teen girls, dismissed: they’re angsty! They’re emotional! They need to grow up a bit—stop crying, smarten up, refine their taste—before they’re ready to participate in creative practice. In ‘How It Feels’ (featured in the same issue) Jenny Zhang writes, ‘Like so many other fourteen- year-old girls, I was told that my problems were minor, my tragedies imaginary’ and then later that ‘everything is embarrassing’. These two archetypal anxieties coexist so unhappily in many girls’ and young women’s consciousnesses: on the one hand, a feeling that the world does not value your experience; and on the other, a sense that the world is right and that you don’t in fact have anything of significance to say. Gevinson has said herself that she will never be more biologically emotional than she was at 17, but hey: isn’t this hormonal tornado the perfect weather for artistic exploration?

What’s particularly significant about Gevinson’s guest-edit and of other moments like this—of very young women being let into the mainstream, onto the pitch of the cultural elite like the editorial board at Poetry magazine—is that they are the direct result of self driven, often collaborative creative projects that explore the teen female experience, and as such they have made it into the giddy realms of serious literature on their own terms.

Virginia Woolf famously said that a woman needs ‘money and a room of her own’ in order to pursue her art, but there’s now a third element in the equation that seems equally fundamental: the internet. This is a generation of girls who have come of age online, and the movement is both made possible by the web and also framed by its aesthetic. These teens are trawling Instagram, watching YouTube tutorials on how to draw comics, playing around with InDesign, and—you guessed it—posting angsty poetry on their blogs. As 23-year-old artist Arvida Byström has said: ‘To me, [the internet] was a little window out of a very closed room of teenage depression because I could be online and still meet people, even though I felt like shit. Finding Tumblr was a big deal, and that was when I started developing my particular aesthetic. It’s great for finding subcultures, which is important for young people who have more time, and are more bored, and who have to stay at their parents’ place or at home.’ (Again, note the importance of angst—seriously.)

Omar Kholeif argues in his book You Are Here: Art after the Internet that nowadays ‘the web browser is a gallery in and of itself ’. It makes sense, then, that the insistence by this movement on publishing work online (sometimes solely online) unsettles traditional notions of what ‘matters’—it denies any assertion that to be published in a traditional literary journal or art magazine is more valid or a matter for congratulation than to be published on a website. In such times, it’s not surprising that online exhibition spaces such as Art Baby Gallery, which ‘celebrates multimedia artists in the beginning stages of their career through monthly solo exhibitions’, are thriving. Art Baby supports and promotes what they term yibas (young internet-based artists) and provides a platform where exhibitors such as Miza Caplin, Maja Malou Lyse, Emma Orlow and Ayqa Kahn can show works that relate directly to the experience of being young and female.

At their best, works (not just poetry—art and publishing, too) by this new generation of young women are unashamedly drenched in the aesthetic of typical teen girlishness. In one Instagram post, Byström sits on the floor in a corner of a well-lit room, face squashed in a scowl, as she sports faded blue hair and a slogan T-shirt that says ‘why are you still talking’. Chloe Wise painted a series of ‘selfies’ for her project Literally Me, and then shared pictures on social media of her posing next to the works wearing the same clothes.

In her debut collection i will never be beautiful enough to make us beautiful together, poet Mira Gonzalez writes in a distinctly unemotional way that she feels ‘slightly anxious about nothing in particular’. These works and many like them completely embrace the stereotypes of the moody and disinterested or shallow and kitsch adolescent. They knowingly appropriate the language of this stereotype, in a way that injects it with a mysterious power: not only are these women able to critique your preconceptions, but they can do it in away that genuinely says something important and sincere about the way it feels to experience youth today.

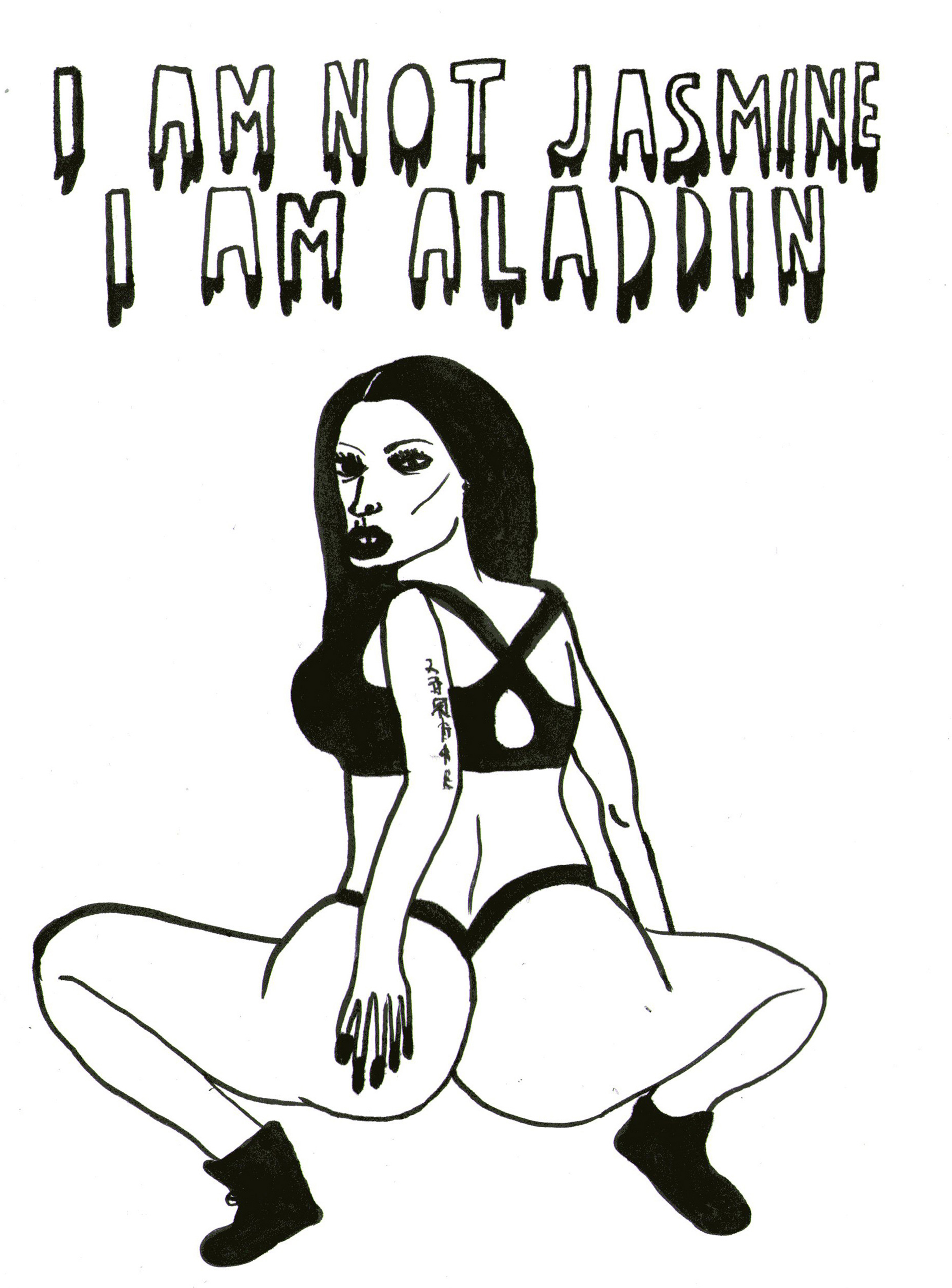

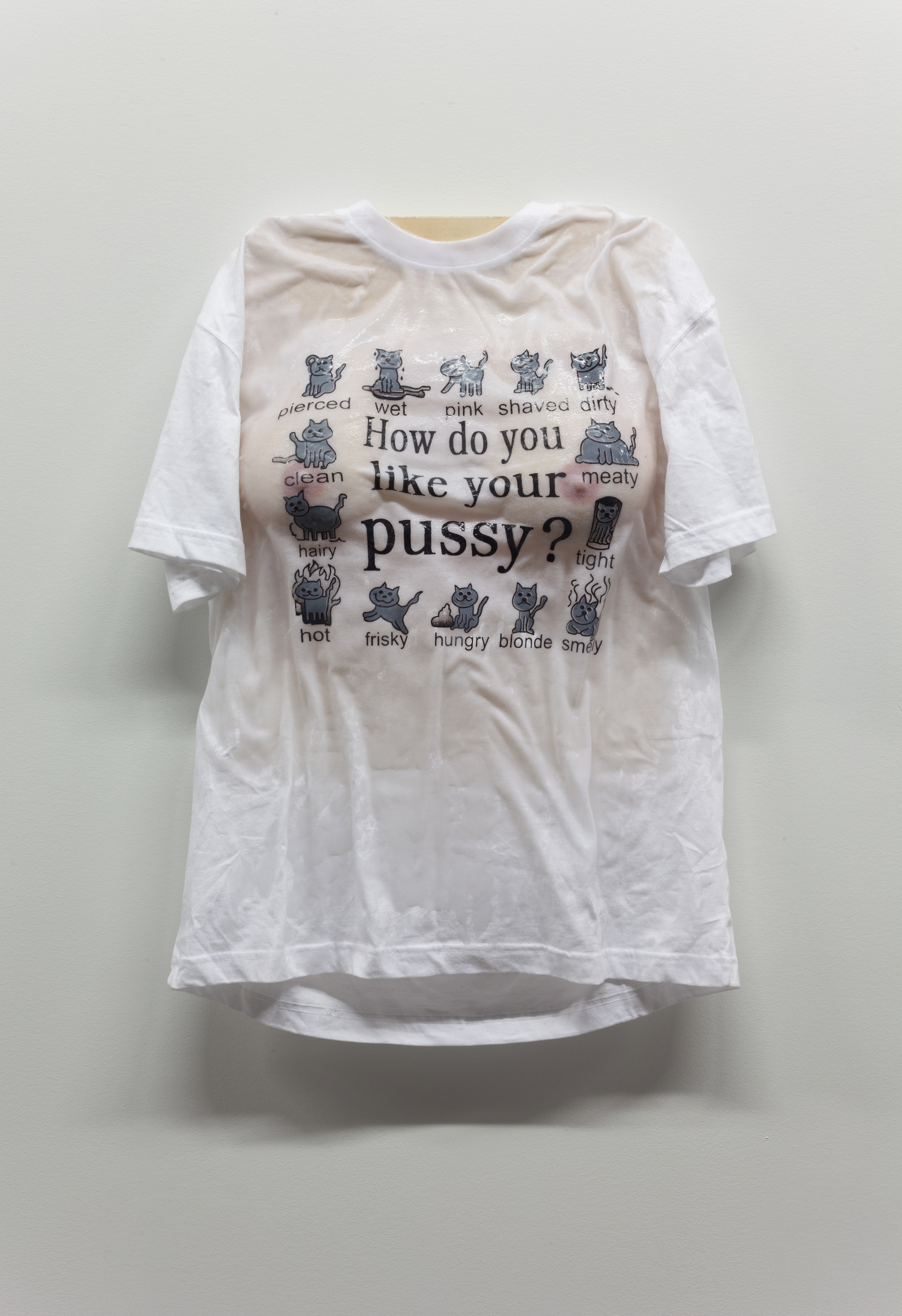

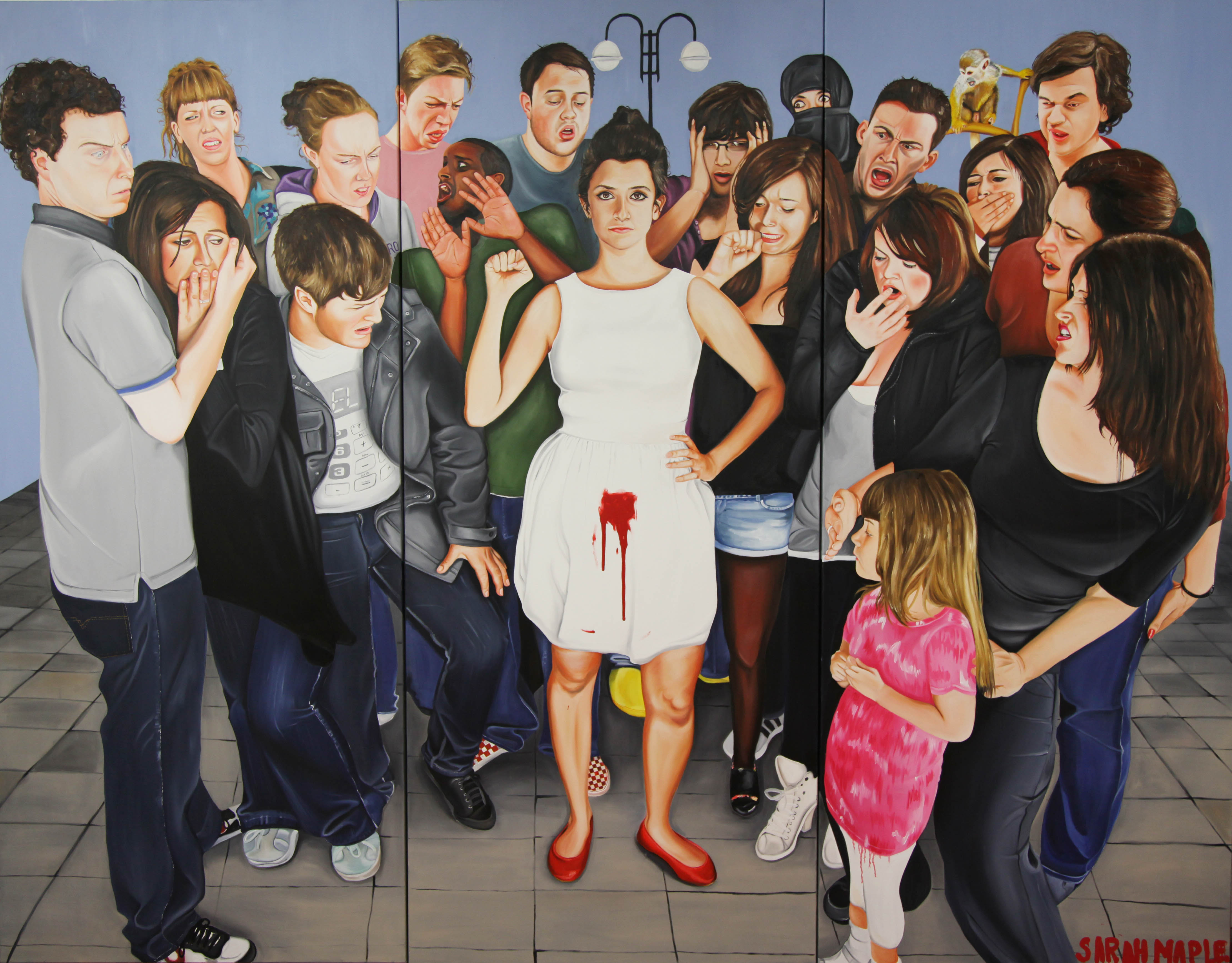

There is often an exploratory approach to medium, with mainstays of the movement such as photographer Petra Collins also flirting with collage, illustration and watercolour. Pastel colours (especially baby pink), bedrooms, underwear, body hair, female figures and nods to pop culture (see Sarah Maple’s painted portrait of Britney famously shaving her head) feature heavily. There are a lot of pink cotton pants and images of girls lounging about in their bedrooms. There’s a resurgence of interest in comics, zines and illustration. Hashtags, memes, abbreviations and stupid jokes are par for the course: a visual and written language (no longer unique to online spaces) that seamlessly drifts between articulating strong political beliefs and loling at a picture of a cat. Works can be confessional and sincere (taking notes from Sylvia Plath and Tracey Emin) or completely tongue-in-cheek. Some of it is engaged explicitly with traditionally feminist issues such as abortion, menstruation, sexual autonomy, depression and portrayal of women in the media, but just as much is about identity and growing up—about all those things that a modern teenager is concerned with: self-consciousness, rejection, friendship and a developing sexuality.

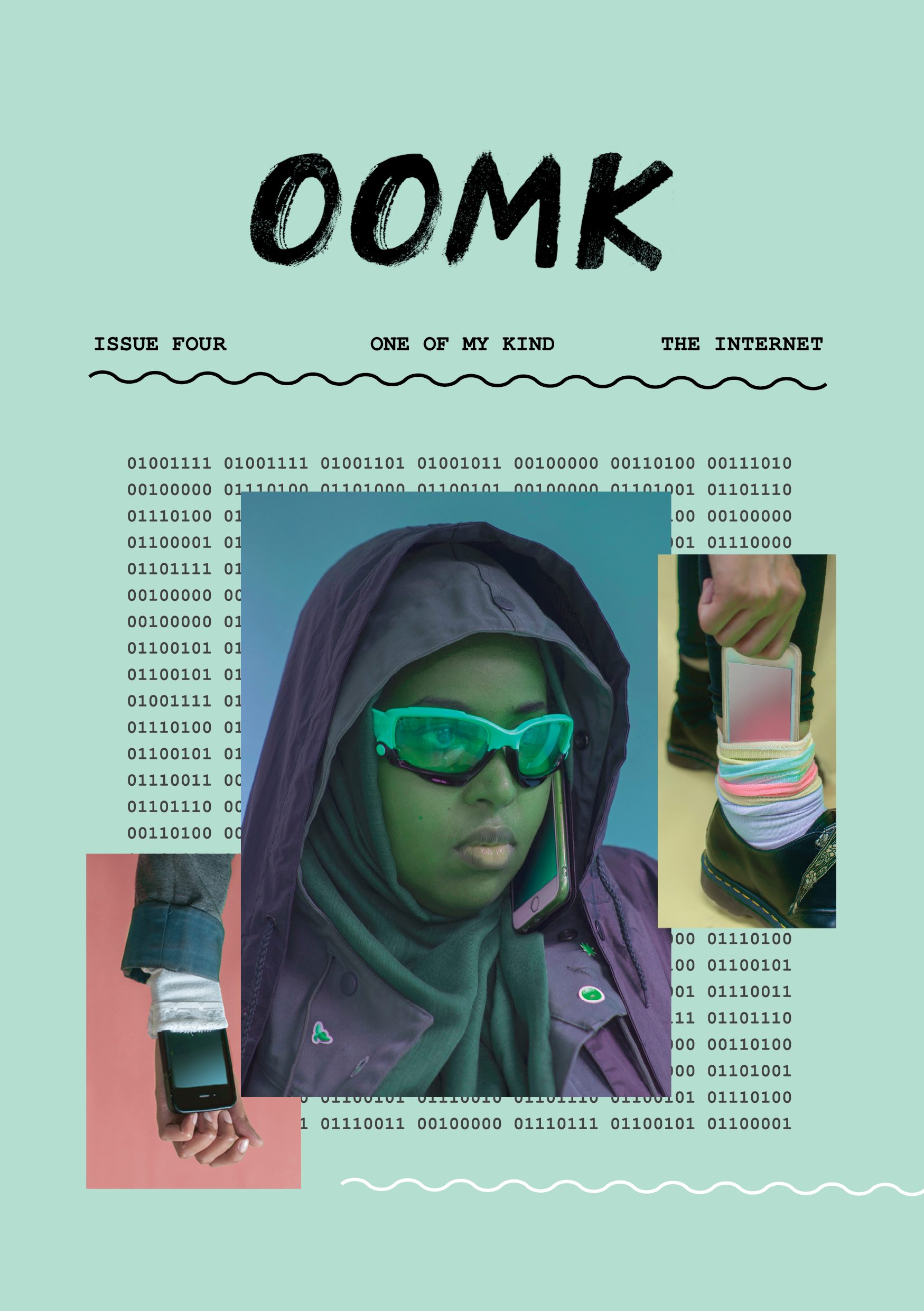

The gradual rejection of falsely perfected female bodies and vapid content in women’s and mainstream media has given rise to a type of publishing that rebels fiercely against these things, and to a new breed of zine makers and young self-publishers. The all-female teams behind such publications as One Of My Kind (OOMK), Girls/Club and Pink Spex are working to diversify the representation of female experience in print. The Riot Grrrl punk movement of the 1990s and its association with diy ethics is a clear precursor to some of these activities, and yet these magazines are polished, with a professional standard of design and editorial content that’s often achieved by self-teaching the necessary skills of Adobe InDesign and photography.

Georgia Murray, founder and editor of Girls/ Club, a biannual magazine dedicated to celebrating the creative outputs of her contemporaries, says of the international zine publishing world: ‘There’s a feeling at the moment between young women—a community—and it’s created by a disillusionment with existing publications. What Girls/Club boils down to is offering mutual support, wanting to big up your female contemporaries, and to shine a light on the talent, creativity and brilliance of those around you.’ OOMK, made by Sofia Niazi, Rose Nordin, Heiba Lamara and Sabba Khan, works similarly to promote female creative work but is particularly keen to showcase that of young Muslim women. The highly visual, small-press publication says that its content ‘pivots on the imaginations, creativity and spirituality of women’ and that it explores activism, faith and identity. Pink Spex is a ‘collection of drawings’ made by Hannah Prebble, Jordana Globerman and Marja de Sanctis that showcases female takes on sexuality. It’s full of masks, knives, ominous shadows and bums in sexy underwear. These are publications, once perhaps thought of as niche, that all sold out their first issues due to the attention garnered on the web, and are examples of work (like most of the work featured here) that did not and would not have been able to have mass exposure in a pre-internet world.

As well as facilitating the pursuit of aesthetic or cultural knowledge, the internet offers a platform by which the voices of historically marginalized women can come together and be heard. These aren’t always in harmony, of course—debate (friendly or otherwise) is as crucial in this as in any movement. But intersectionality—the view that people experience oppression in varying degrees of intensity depending on a combination of factors which can include gender, race, class, ability and ethnicity— increasingly shapes feminist dialogue, especially online.

Amandla Stenberg’s video on cultural appropriation, ‘Don’t Cash Crop On My Cornrows: A Crash Discourse on Black Culture’, has been viewed on YouTube nearly 2 million times; has sparked a debate about the topic in international media with articles in the Huffington Post, the Independent, the Telegraph and New York magazine; and is just so eloquent and well argued that you can hardly believe the context in which it was made: namely, for Stenberg’s high-school history class (it gives a shout-out to her teacher, Deb, at the end), because the actor and activist is just 16 years old.

Stenberg is also a contributor at Art Hoe, a popular online movement founded by 15-year old gender-fluid Mars, which encourages young people of colour to embrace art and visual culture and show their own creative work. The movement’s name ‘hoe’ is, Mars explains, a typically aave (African American Vernacular English) derogatory slang term that refers to a promiscuous woman—particularly if that woman is non-white—and Mars argues that using this term in an arbitrary way ‘diminishes its harmful origin in light of something better’. In this way, the movement is adopting the same approach as the artists discussed above: it appropriates the aesthetic or the language of the very stereotype that was used to marginalize the group producing the work, and then betters it. Art Hoe curator Anisa Olufemi M says of the aims of movement, ‘it’s about trying to help other artists of colour be recognized for their hard work, and to give them a safe place for raw self expression.’

At the heart of all of this—of the poetry, the art, the publishing—is a determination by young women to tell their own stories; to demand equal representation across the board in contemporary creative practice. Its effect is to force the suspicious to acknowledge young female experience as creatively fertile, valid and of interest to the rest of the world.